Distribution of middle-class women’s time between paid and unpaid work in West Africa: a multinomial analysis

Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar, Sénégal

Email : coulibalynarmand@gmail.com

Orcid id: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-4852-4141

Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar, Sénégal

Email : mamecheikhanta.sall@ucad.edu.sn

Orcid id: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3145-1990

Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar, Sénégal

Email : adama.sow@ucad.edu.sn

Orcid id: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5898-336X

Université Abomey Calavi, Benin

Email :denis.acclassato@yahoo.fr

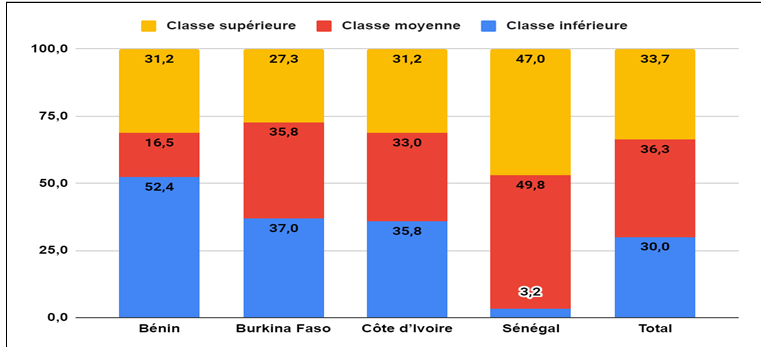

Résumé : Le travail domestique non rémunéré est aujourd’hui un aspect central dans la vie familiale et prend une large partie du temps des femmes de la classe moyenne. Cet article analyse l’arbitrage que ces dernières font, dans la répartition de leur temps, entre le travail domestique et la participation au marché du travail rémunéré. Pour mener à bien cet objectif, nous optons pour un modèle logit multinomial qui permet d’identifier les déterminants de la probabilité qu’une femme de la classe moyenne alloue son temps au travail domestique non rémunéré ou au travail rémunéré. Les résultats montrent qu’au Bénin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire et Sénégal, les femmes qui allouent leur temps de travail aux tâches familiales ont 35% et 45% de chance respectivement d’effectuer un travail non rémunéré qu’un travail salarié et indépendant. La répartition du temps entre travail rémunéré et travail domestique de la classe moyenne féminine est déterminée par le nombre d’enfants en bas âge, la proximité d’une garderie et le statut professionnel de l’époux. Cependant, une analyse des résultats au niveau de chaque pays, pris individuellement, met en évidence d’autres facteurs susceptibles d’expliquer l’allocation du temps de travail des femmes dans les ménages à savoir le statut matrimonial, l’âge de la femme, la classe sociale. À la lumière de ces résultats, une politique de promotion de services de garde d’enfants de proximité ciblant les foyers de concentration des femmes de la classe moyenne concernée corrigerait ce déséquilibre d’allocation de temps de travail.

Mots-clé : Allocation du temps de travail, Travail domestique, Marché du travail.

Abstract : Unpaid domestic work is now a central aspect of family life and takes up a large portion of middle-class women’s time. This article aims to analyse the trade-offs these women make in allocating their time between domestic work and participation in the paid labour market. To fulfil this objective, we use a multinomial logit model to identify the determinants of the probability that a middle-class woman will allocate her time to unpaid domestic work or paid work. The results show the women in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal who allocate their working time to family tasks are 35% and 45% more likely, respectively, to engage in unpaid work than in paid and self-employed work. The allocation of time between paid work and domestic work among middle-class women is determined by the number of young children, the proximity of a daycare centre and the professional status of the husband. However, an individual country-level analysis of the results highlights other factors that may explain women’s allocation of time in households, including marital status, age and social class. In view of these results, a policy promoting local childcare services targeting households with a high concentration of middle-class women would correct this imbalance in the allocation of working time.

Keywords: Allocation of working time, Domestic work, Labor market.

Références bibliographiques

Abington, C. (2020). The Impact of Government Policies on Female Labor Force Participation Rates. Journal of Business & Economic Policy, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.30845/jbep.v7n4p2

Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie et AFRISTAT (2019). Enquête Régionale Intégrée sur l’Emploi et le Secteur Informel (ERI-ESI), 2018. Rapport final. Dakar, Sénégal. ANSD et AFRISTAT.

Alfers, L., Lund, F. & Moussié (2018). Informal Workers & The Future of Work: A Defence of Work-Related Social Protection. WIEGO Working Paper No. 37. Manchester: Women in Employment Globalizing and Organizing.

Altonji, J. G. & Pierret, C. R. (1997). Employer Learning and Statistical Discrimination. NBER Working Paper N°6279. https://doi.org/10.3386/w6279

Amin, S. M., Rameli, M. F. P., Ab Hamid, N., Razak, A. Q. A., & Abd Wahab, N. A. (2016). Labour supply among educated married women influenced by children. Journal of Global Business and Social Entrepreneurship (GBSE), 2(4), 110-7.

Amin, S. M., Rameli, M. F. P., Othman, A., Hasan, Z. A., & Ibrahim, K. (2017). Decision to work by educated married women. Advanced Science Letters, 23(8), 7702–7705. 10.1166/asl.2017.9557

Arvan, M. L., Denunzio, M. M., Shen, W. & Shockley, K. M. (2017). Disentangling the Relationship Between Gender and Work–Family Conflict: An Integration of Theoretical Perspectives Using Meta-Analytic Methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(12), 1601–1635.

Becker, G. S. (1965). A Theory of Allocation of Time. Economic Journal, 75(299), 493–517. https://doi.org/10.2307/2228949

Becker, G.S. (1985). Human Capital, Effort and Sexual Division of Labour. Journal of Labour Economics, 3(1, Part 2), S33–S58. https://doi.org/10.1086/298075

Buisson, M. (2012). Allocation du temps de travail des femmes au Sénégal – Travaux domestiques et activités génératrices de revenus. halshs-00673119. Etudes et Documents, CERDI.

Byron, R. A. & Roscigno, V. J. (2014). Relational Power, Legitimation, and Pregnancy Discrimination. Gender & Society, 28(3), 435–462. DOI : 10.1177/0891243214523123

Dunatchik, A., Gerson, K., Glass, J., Jacob J., Sstritzel, H. (2021). Gender, Parenting, and the Rise of Remote Work During the Pandemic Implications for Domestic Inequality in the United States. Gender & Society, 35(2), 194–205. 10.1177/08912432211001301

Fafchamps, M. and Quisumbing, A. R. (2003). Social Roles, Human Capital, and the Intrahousehold Division of Labor: Evidence from Pakistan. Oxford Economic Papers, 55 (1), 36-80.

Fernando, W.D.A. & Cohen, L. (2014). Respectable Femininity and Career Agency: Exploring Paradoxical Imperatives. Gender, Work and Organization, 21, 149-164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12027.

Fontaine, I. (2018). L’effet causal du nombre d’enfants sur l’offre de travail des mères : le cas de la France métropolitaine et de ses départements d’outre-mer. Revue économique, 69(5), 869–898. https://doi.org/10.3917/reco.695.0869

Greenwood, J., Seshadri, A., & Yorukoglu, M. (2005). Engines of liberation. The Review of Economic Studies, 72(1), 109-133. https://doi.org/10.1111/0034-6527.00326

Gronau, R. (1977). Leisure, Home Production, and Work-The Theory of the Allocation of Time Revisited. Journal of Political Economy, 85(6), 1099-1123. https://doi.org/10.1086/260629

Hakim, C. (1996). The Sexual Division of Labour and Women’s Heterogeneity. The British Journal of Sociology, 47(1), p. 178-188. https://doi.org/10.2307/591124

Hakim, C. (2004). Key Issues in Women’s Work: Female Diversity and the Polarisation of Women’s Employment. Athlone Press.

Hakim, C. (2006). Women, careers, and work-life preferences. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 34(3), 279-294. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880600769118

Herrera, J. & Torelli, C. (2013). Travail domestique et emploi : quel arbitrage pour les femmes ? Les marchés urbains du travail en Afrique subsaharienne, IRD édition.

Keck, W. & Saraceno, C. (2013). The Impact of Different Social-Policy Frameworks on Social Inequalities among Women in the European Union: The Labour-Market Participation of Mothers. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 20(3), Pages 297–328, https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxt005.

Kes, A. & Swaminathan, H. (2006). Gender and Time Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Working Paper No. 73, The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Khandker, S. R. (1987). Labor Market Participation of Married Women in Bangladesh. The Review of Economics and Statistics, MIT Press, 69(3), 536-541.

Khanie, G. (2019). Education and labor market activity of women: The case of Botswana. Journal of Labor and Society, 22(4), 791-805. : https://doi.org/10.1111/lands.12455

Lundberg, S. and Pollak, R. (1996). Bargaining and Distribution in Marriage. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(4), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.10.4.139

Mandel, J. L. (2004). Mobility Matters : Women’s livelihood Strategies in Porto Novo, Benin. Gender Place and Culture. 11(2) . 257-287.

Manser, M. & Brown, M. (1980). Marriage and Household Decision-Making: A Bargaining Analysis. International Economic Review, 21(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/2526238

Mathieu, M. (2019). L’espace familial et l’offre de travail des femmes : une synthèse des contributions théoriques sur le sujet. Haïti Perspectives, 7 (1).

Menon, N., & Rodgers, Y. V. (2018). Women’s labor market status and economic development.

Mojumder, M. (2020). The Role of Women in The Development of Society. Journal of Critical, 7(2).

Morosow, K., & Kolk, M. (2020). How does birth order and number of siblings affect fertility? A within‐family comparison using Swedish register data. European Journal of Population, 36(2), 197–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680‑019‑09525‑0

Mosomi, J. (2019). An empirical analysis of trends in female labour force participation and the gender wage gap in South Africa. Agenda, 33(4), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2019.1656090.

Nagac, K. & Nuhu, H.S. (2016). The Role of Education in Female Labour Force Participation in Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Economics and Finance, 7(1), 56-62.

Olowa, O. & Adeoti, A.I. (2014). Effect of Education Status on Women on their Labour Market Participation in Rural Nigeria. American Journal of Economics, 4(1), 72-81.

Omotoso, K. O., & Obembe, O. B. (2016). Does household technology influence female labour force participation in Nigeria? Technology in Society, 45, 78-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2016.02.005

Pfau-Effinger, B. (1998). Gender cultures and the gender arrangement—a theoretical framework for crossnational gender research. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 11(2), 147-166. doi:10.1080/13511610.1998.9968559.

Sofer, C. (2005). Choix relatifs au travail dans la famille: la modélisation économique des décisions. Travail et emploi, no 102, p. 79-89.

Tilcsik, A. (2021). Statistical Discrimination and the Rationalization of Stereotypes. American Sociological Review, 84(2), 248–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420969399.

Usman, O. & Sanusi, A. (2016). Education and Labour Force Participation of Women in North Cyprus: Evidence from Binomial Logit Regression Model. Munich Personal RePEc Archive, Paper No. 77140.

Viollaz, M. (2018). Enforcement of labor market regulations: heterogeneous compliance and adjustment across gender. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 7(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40173‑018‑0095‑7

Woolley, F. (2011). Taxation and Gender Equity: A Comparative Analysis of Direct and Indirect Taxes in Developing and Developed Countries. Edited by Caren Grown and Imraan Valodia. Routledge. Feminist Economics, 17(2), 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2011.573489.